Last week, as the sun was rising over Turkey, police across the country raided homes and offices of those suspected to be linked with anti-government protests. Prime Minister Recep Erdoğan’s handling of protests broached a new level of force as the daybreak round-up targeted those in media organizations. Left-leaning news outlets Atılım Newspaper, Etkin News Agency, and Özgür Radyo were all raided, with some employees taken into custody.

The protests, which started over government plans to build an “Ottoman barracks-style” mall on Gezi Park, one of Istanbul’s last public parks, have moved beyond municipal discontent, raising the political stakes and outraged drama of the standoff.

The targeting of journalists, both in the June 18th raid and during recent rallies, seems to substantiate claims of heavy-handedness often made by opponents of the center-right Prime Minister and his Justice and Development Party. Elected in 2003 on a populist wave that took advantage of Turkey’s buoyant economy and a sense of neglect among more religious voters, Erdoğan has been a controversial figure throughout his tenure and has repeatedly come under pressure for attacking the press. Under Erdoğan’s leadership. radical left-wing groups – particularly Kurdish organizations – have been consistently targeted for government scrutiny.

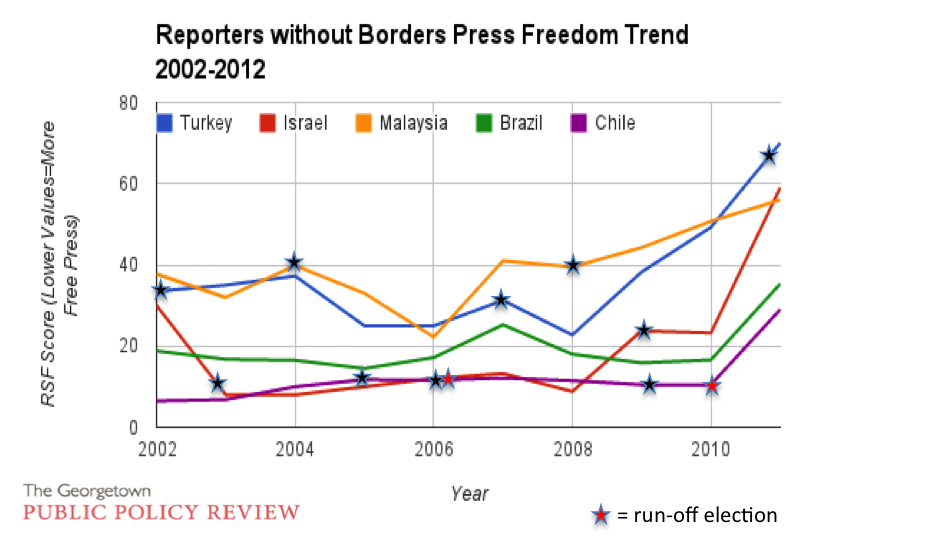

The morning raid against journalists appears to be part of a larger trend in Turkey and other rising, and even solidly, middle-upper income countries. Data from the non-profit Reporters Without Borders confirms what many observers have noted anecdotally: over the last ten years, press freedom has been decreasing in Turkey.

The stars on the graph below denote election years. “Press freedom” rankings are inherently subjective, but include indicators such as self-censorship by journalists, threats and attacks against the press, a country’s legal framework, and imprisonment of reporters. A lower ranking is better, so an upward trend suggests fewer free speech rights. Israel, Brazil, Chile, and Malaysia, which have also seen popular protest movements and experienced similar levels of growth as Turkey, are included for comparison.

Growth and Democracy

The fact that Turkey’s economy has grown even as its press rights have declined factors into a wider debate about the interplay between economic growth and political institutions.

Some economists claim that investments in human capital can have an impact on economic growth, and thus authoritarian leaders wielding good public policy can produce positive GDP results without citizen consent.

The most visible opponents of this theory are Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, whose popular book, Why Nations Fail, built upon previous research claiming that authoritarian leaders run “extractive” political institutions. In this scenario, leaders may help the state grow, but only to transfer most of the benefits to themselves and their supporters, which ultimately hinders economic growth.

There are many offshoots of this discussion, but the correlation between rising economic prosperity and institutional governance has influenced how global donors think about growth. Indeed, there does seem to be a correlation between improvement in democratic rights and growth, but the connection is not clear-cut. The graphs below shows the trend between GDP per capita and Freedom House’s civil liberties score for countries that, like Turkey, have seen stable growth rates and notable political changes.

Is Turkey a Press Prison?

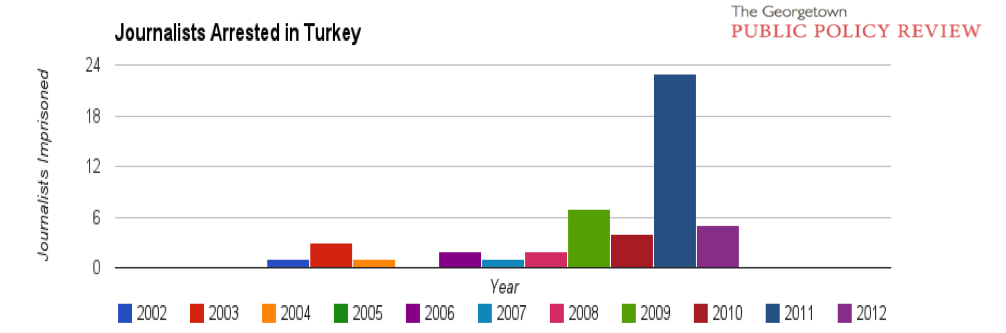

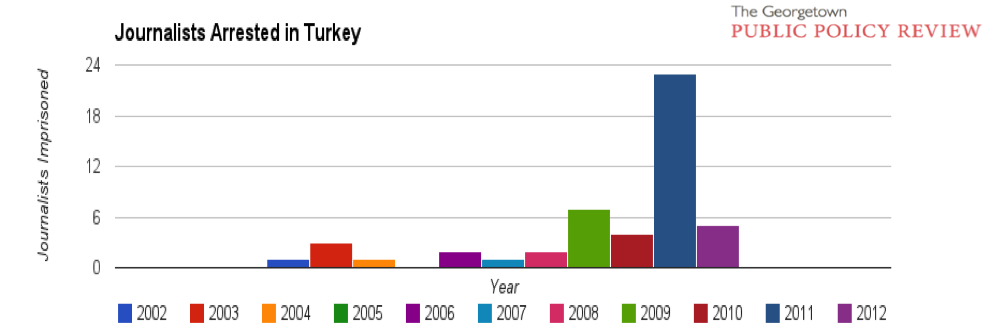

Counting arrested journalists can be a tricky endeavor. In some cases, reporters are part of organizations that the government might have a legitimate reason to target. As Turkish journalist Yavuz Baydar noted in 2011, in many countries there are journalists in prison, often for breaking criminal laws, but this does not constitute an attack on the freedom of expression outright.

Through a comparison of “arrest lists” from the Committee to Protect Journalists, Reporters Without Borders, and the Turkish Journalist Syndicate, and search of Lexis-Nexus from 2002-2012, a picture of journalist arrests comes together. This data is by no means comprehensive, and figures are difficult to corroborate – each of the aforementioned groups lists a different number of arrests each year – but all have reported a steady increase in arrests.

Many of the groups list aggregate journalists imprisoned, so if a journalist was arrested in 2004, but remains in prison in 2005, she is counted for both years. This kind of counting has led some organizations, such as OSCE, to make attention-grabbing statements about how many journalists have been imprisoned in Turkey. However, in the chart below, I have counted each time a journalist was imprisoned for that year. In many cases, those arrested two or three years ago remain incarcerated. Imprisonment hit a high point in 2011, with 23 journalists charged and imprisoned. The graph below aggregates reports of press imprisonment to clearly show recent trends.

Protecting the Fourth Estate

The rise of nation-wide popular protest movements over the last three years exemplifies both the limits of responsive politics and a greater understanding of its potential. These graphs present a quick and easy view into press freedom, yet there are many other factors – such as short term apprehensions, extended police questioning, and other forms of detention – that inhibit reporting. Additionally, there are systemic problems of which these numbers are simply symptoms. The censor of Turkish journalists coverage along the Syrian border and the monopolization of mainstream media outlets, have difficult-to-quantify effects on expression, but a clear impact.

In a seemingly default democracy era, when more countries are democratic than not, how leaders react to their citizenry is critical if the positive correlation between GDP growth and civil liberties is to be born out. Press freedom has improved substantially across Asia and Africa, but the countries at the top of the Reporters Without Borders index have remained the same for years. Even as the memory of last week’s morning raid on news organizations fades, the data remain. It will be important for policy makers, voters, and those studying growth and governance to keep tabs on these individual moments that comprise history.

Jacob Patterson-Stein is a second year Master of International Development Policy student. Prior to attending McCourt, Jacob worked for Thomson Reuters in Washington D.C., the More than Me Foundation in Liberia, and in a rural public school in South Korea. He spent summer 2013 working for the Support for Economic Analysis Development in Indonesia (SEADI) project in Jakarta.

1 thought on “The Numbers Behind Press Freedom and Economic Growth in Turkey”

Comments are closed.