In the opening remarks of his confirmation hearing, soon-to-be Secretary of State John Kerry quoted elder statesman Henry Kissinger: “Never before has a new world order had to be assembled from so many different perceptions, or on so global a scale.” As Senator Kerry noted, the quote is as true now as it was in 1994 when Kissinger wrote it. Part One in our International Affairs series highlighted the fact that 2013 will be a year to deal with simmering disagreements before they boil over, to adjust policies to a world that is finally getting comfortable with globalization, and to recognize the limits and benefits of the divergent power dynamics about which Kissinger wrote. Part two of our series picks up where part one left, with a few of the events we will be watching in the coming year.

Enjoy,

Jacob Patterson-Stein

In this article:

Bad Jobs at Better Wages? – by Jacob Patterson-Stein

War and the Chinese Gambit – by Jason Kumar

Mapping for Development – by Rachel Wood

Bad Jobs at Better Wages?

The demand for cheap clothes is going to continue through 2013 and the theories of competitive and comparative advantage are not going anywhere either. What may change is the commonly held belief that, as Paul Krugman suggested in the 1990s, “bad jobs at bad wages are better than no jobs at all.”

When Krugman penned that line, he was responding to the sense of revulsion that many Americans feel when they find out that cheap clothes and inexpensive goods are cheap and inexpensive for a reason. As wages steadily rise, there is a growing awareness that governance, labor rights, and employer responsibility are critical for growth in the developing world. A series of high profile factory fires in Pakistan and Bangladesh, several exposés into Foxconn (the firm that produces many of Apple’s products in China), and increased efforts to organize low-skilled factory workers in the developing world may kick-start the move toward better labor conditions in 2013.

Recent achievements have been minor but notable. In Bangladesh, women have successfully lobbied one of the largest garment industry groups to implement better working conditions. Factory workers met with the US Ambassador to Bangladesh to voice their concerns and suggestions for better labor conditions—despite the fact that official labor organizing still requires government sanction. Foxconn pledged to raise wages and improve working conditions under pressure from workers, Apple, and consumers. Indeed, recent data suggests that these recent events are part of a larger trend. China saw real average wages more than triple from 2000 to 2010, and average monthly wages almost doubled in Asia overall during the 2000 to 2011 period, according to the ILO. The fears of a “race to the bottom,” which often capture hearts and minds, have long been proven wrong. Practical policy seems to be catching up to the work of academics, such as the Peterson Institute’s Kimberly Ann Elliott and Harvard’s Richard Freeman, who have long suggested that labor rights increase productivity.

The US is currently negotiating a Trans-Pacific Partnership to create a free trade union among Pacific nations, which could affect labor conditions in participating countries such as Vietnam. However, weak governance in places such as Pakistan and Bangladesh and the lack of incentives to improve working conditions in most countries will not disappear in the next year. What will change is the more active and constructive role that workers groups will play in 2013. Labor accreditation groups, the West’s watchdogs for labor conditions, are also taking note of their failures and instituting policies to become more diligent. This might be the year that bad jobs at bad wages do not have to mean bad working conditions.

War and the Chinese Gambit

The high tensions between China and other nations in the region will likely come to a head in the coming year. After a period of strong economic growth and increased influence in its region, China’s economy is beginning to slow down just as a new administration begins its transition to power. Combined with increased pressures from the US and other nations in the region, China’s new administration will soon feel the need to establish its strength by reclaiming disputed territory and potentially turning the protracted anxieties and posturing into something much harsher.

In Southeast Asia, the US and China are wrestling over influence of nations in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) trading bloc. China has long had strong trade and political influence over ASEAN nations and has exerted claims over many land and sea resources there. This has recently included the resource-rich islands in the South China Sea that the ASEAN nations are now attempting to re-establish as their own. The stand-off between China, the US, and ASEAN over these islands has culminated in naval posturing, the arrest of Chinese fishermen trespassing on ASEAN-held waters, and strong rhetoric from all sides that has done little but limit future strategic options. As the strong US military presence near the South China Sea is forestalling the possibility of this dispute erupting into all-out war, China’s leadership is left without any way to move this conflict forward. Backed into a corner, China may seek out alternative ways to establish its regional presence.

To this end, the new Chinese administration will likely take advantage of its ongoing conflict with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. While both nations are capable of exercising strategic patience over these uninhabited and unremarkable islands, a series of absurdly escalating engagements—reminiscent of Dr. Suess’ “The Butter Battle Book”—has pushed an otherwise centuries-old land dispute to the brink of national-level armed conflict. The spark to this powder-keg could be that China’s new Prime Minister, Xi Jinping, is in the tenuous position of having to assert himself as a unifying force in the administration during his transition into power. As such, a show of Chinese force to any US or Japanese assertion of influence over the Senkakus may be his only option, as most other options may cause him to appear weak and incur great political costs.

If protracted conflict is to be avoided, the US, Japan, and ASEAN must treat China very carefully and engage in talks that break the cycle of action and reaction that simply move all parties towards all-out war.

Mapping for Development

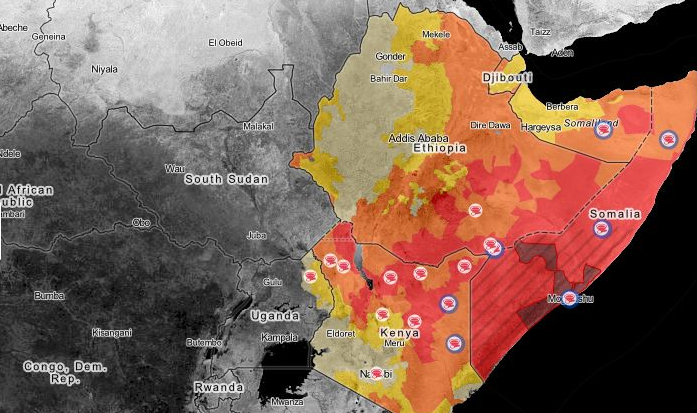

The number of NGOs and companies utilizing open-source data mapping tools for international development purposes is expected to swell in 2013. The emergence of open data tools signals a growing effort to increase participation, transparency, and networking within the development field.

Geographic information systems, or GIS, are increasingly effective for real-time updates; from disaster relief efforts in Port-au-Prince, Haiti to sourcing local feedback on farming programs in Karonyi, Rwanda. Following the lead of NASA, USAID, the World Bank, and InterAction, the United Nations Development Programme launched its own open data site late last year with information on its more than 6,000 projects. The proliferation of other services, including Ushahidi and Development Seed, which offer crowd sourcing and data visualization tools, plus Open Street Maps and Harvard’s WorldMap, which provide previously unavailable geographic information, are literally putting rural villages on the map.

Development specialists hope that growing program participation will empower local communities while offering data to improve government accountability and research. Google Maps’ recent unveiling of park and street names in North Korea, the world’s most hermetic country, illustrates the availability of untapped data among “citizen cartographers.” It seems international industries are only beginning to harness the power that instant access to formerly unavailable information offers.

However, just like in more tech-addicted countries, geo-located information carries its own ethical risks; including privacy, confidentiality, and consent concerns. As development-tailored mapmaking evolves in the next few years, the field will likely follow the bumps that older industries endured before reaching a streamlined sophistication. The nascent industry needs to connect the dots among the growing number of mapmakers to provide a comprehensive overview of efforts. Opening the door to this information is a laudable first step. Synchronizing all of the data that is already out there remains the next big hurdle. Hopefully piecing together more comprehensive maps will not be as difficult as folding one up.

Jacob Patterson-Stein is a second year Master of International Development Policy student. Prior to attending McCourt, Jacob worked for Thomson Reuters in Washington D.C., the More than Me Foundation in Liberia, and in a rural public school in South Korea. He spent summer 2013 working for the Support for Economic Analysis Development in Indonesia (SEADI) project in Jakarta.