As we enter the second year of the refugee crisis in southeast Bangladesh, solutions are slow to come and needs remain unmet. The rapid growth of at-risk refugee populations around the world has put international humanitarian institutions to the test, and a critical evaluation of how governments, humanitarian organizations and international institutions have handled the plight of the Rohingya people can serve as a valuable case study for how they manage other long-term refugee crises globally. Former GPPR editor Shane McCarthy traveled to Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh to file this exclusive three-part series on the Rohingya. This is the third and final installment; read the entire series here.

“The whole world is watching what we do next and if we will act.” – Nikki Haley, former US ambassador to the UN, August 2018

Now that the monumental task of collecting data and documenting atrocities against the Rohingya refugees is taking shape, policymakers are turning their attention to long-term solutions to the problem. The task is twofold: demanding justice for the Rohingya and establishing more permanent settlement options. Both tasks are daunting and contentious, and will require buy-in from the refugees, state governments, and the international community.

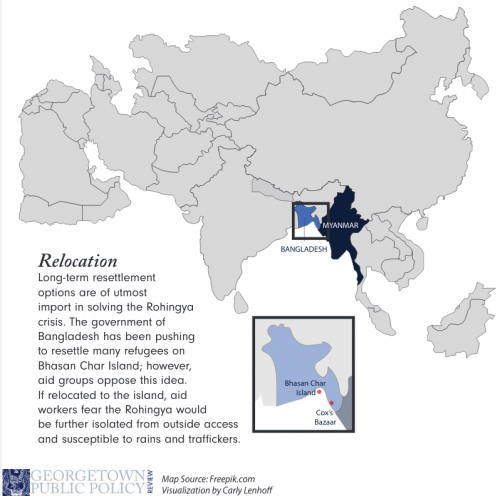

Relocation

With the camps surrounding Cox’s Bazar at capacity, the government of Bangladesh has been pushing for the internal relocation of an initial 100,000 refugees to a new settlement on Bhasan Char Island, across the Bay of Bengal. This plan has met strong resistance from aid groups who have not been able to view conditions on the flood- and cyclone-prone island. If relocated to Bhasan Char Island, the Rohingya would be further isolated from outside access and susceptible to rains and traffickers, aid workers fear. Because their search for solutions is becoming more pressing, the Bangladeshi government has made little effort to consult the refugees about relocation.

Other long-term resettlement options outside of Bangladesh are slowly starting to take shape. Saudi Arabia and Malaysia, which already host a large Rohingya diaspora, have the capacity and resources to host some of the refugees. Other developed nations such as Japan have slowly begun to process applications for asylum. The lack of formal refugee status for most Rohingya has stymied much progress on this front.

International political resolutions

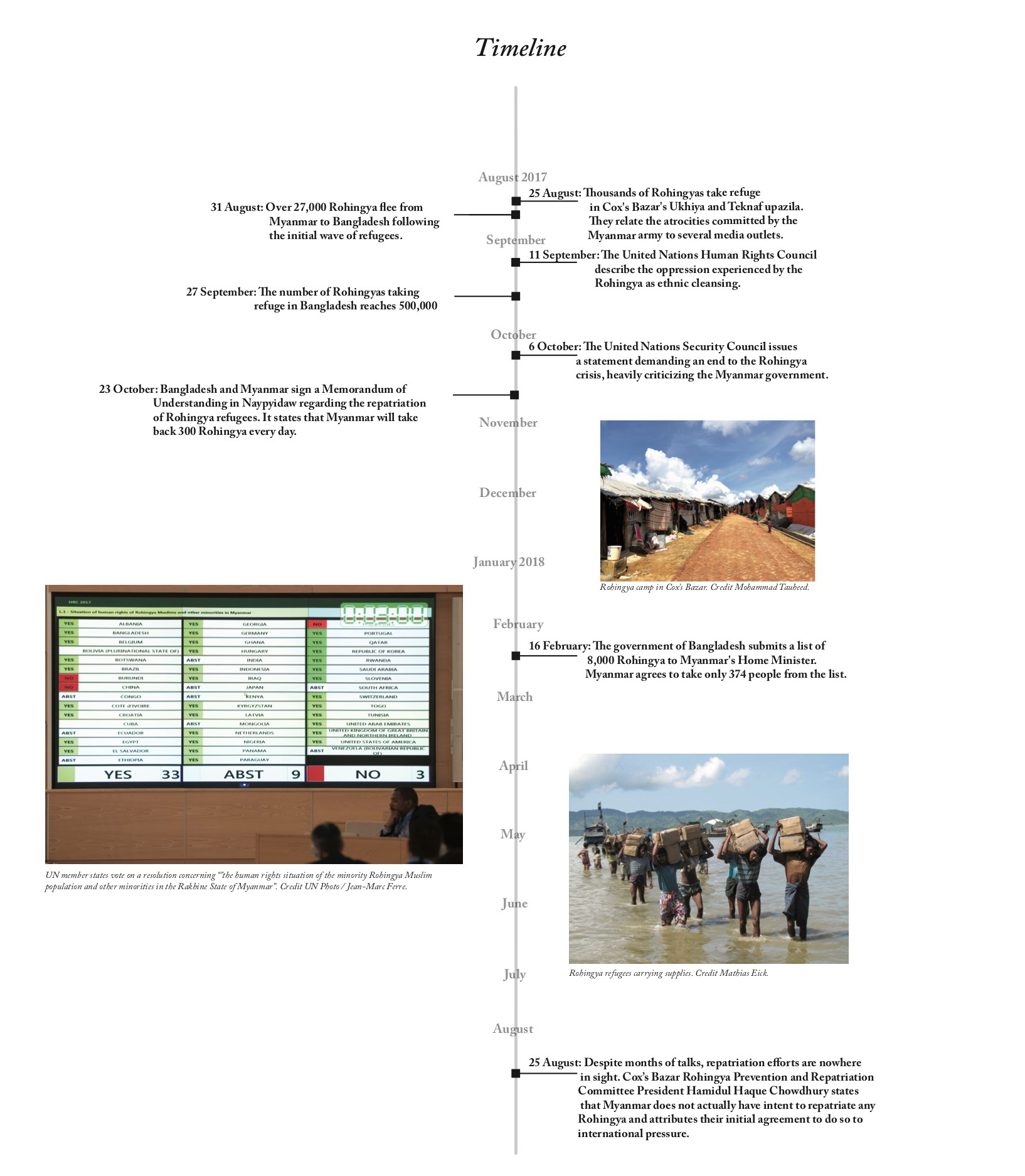

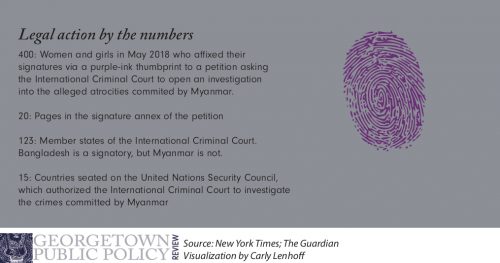

More than a year after the August 2017 atrocities against the Rohingya took place, efforts to hold Myanmar accountable are gaining traction. A recently released report from a UN fact-finding mission, drawing on in-depth research and testimony from hundreds of victims, recommends that the International Criminal Court (ICC) or an ad hoc tribunal investigate and prosecute top Myanmar military officials for genocide. Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Laureate and de facto leader of Myanmar, has committed to follow the recommendations of the UN commission on Rakhine that the late Secretary-General Kofi Annan led. These recommendations include socio-economic development, formal citizenship, and protections for key civil rights and freedom of movement. Unfortunately, it is unclear what actions have been taken thus far.

In November 2017, the Security Council issued a statement calling on Myanmar authorities to “ensure no further excessive use of military force in Rakhine State.” China overruled harsher language and a binding resolution; it shares a disputed border with Myanmar and has extensive investments throughout the country (including in Rakhine). China has recommended its own plan for action, which includes implementing a ceasefire, supporting a bilateral settlement, and providing development assistance to Rakhine. With the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) also calling for action, there are multiple, parallel efforts underway with often competing political objectives. Additionally, any political agreement will require the cooperation of the Myanmar government. Outside access to Rakhine state is strictly limited, making thorough investigations nearly impossible. Visits to the area by UN and other high-level officials are highly staged. Meanwhile, two Reuters journalists remain imprisoned in Myanmar since December 2017 after their attempted reporting on the killing of 10 Rohingya men.

Legal action

After much delay, the fight for legal justice against the Myanmar military is beginning to take shape. In a landmark decision in international law, judges at the ICC ruled that although Myanmar is not a member of the Court, the atrocities in Rakhine come under ICC jurisdiction because the atrocities directly impact the member state of Bangladesh. This decision comes on the heels of painstaking legal and social work among the refugees and the direct petitioning of the court by the Rohingya themselves. In one request, 400 women and girls, mostly illiterate, affixed their signatures with fingerprints. The preliminary investigation by the ICC into the atrocities is now underway though, based on ICC experience in places like Afghanistan, this effort can stretch for years.

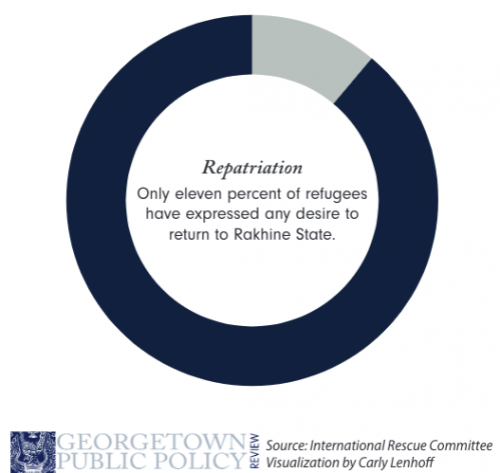

Repatriation

Most of the individuals and organizations see the voluntary repatriation of the Rohingya to Myanmar as the ideal goal. However, numerous factors ensure that this option will be either very limited in scope or not happen at all in the near future. An agreement between the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar last year laid the groundwork for the return of the Rohingya, but this step was seen by outside observers as more of a means of maintaining good relations than addressing the needs of the refugees.

Legal status for the Rohingya in Myanmar is virtually nonexistent, and the government appears unlikely to voluntarily grant it. Conditions on the ground in Rakhine State are difficult to assess because of limited outside access, and there have been reports of the Myanmar military laying mines on the border, making passage back into Myanmar dangerous. Establishing “safe zones” in Rakhine to guarantee safety is a potential but tricky prospect because it would likely require the presence of UN peacekeepers and UNHCR monitors, which many of the Rohingya refugees have called for. With no current guarantee of public safety or recognition, only 11 percent of recently surveyed Rohingya refugees expressed a desire to return.

Human rights versus democracy: The path forward

“The world is waiting and the Rohingya Muslims are waiting.” – Malala Yousafzai, Nobel Laureate, September 2017

More often than not, inaction is the de facto policy choice of the international community when confronting genocide and crimes against humanity. The work to hold perpetrators responsible is getting underway, but lost in the drawn-out process is the struggle, the wait, and the fight to simply live.

As much as the world is appalled by the actions of Myanmar, there is also an added feeling of disenchantment because these crimes were carried out by a country that just made the transition from authoritarianism to democracy under the leadership of a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. There is much to be read into the actions – or lack thereof – of Aung San Suu Kyi, who seems to have limited space for maneuvering because the military still wields significant power. However, hope for Myanmar’s political future or deference to the decisions of the Nobel Committee are no longer reasons to avoid confronting the crisis.

The impending monsoons have not created much urgency for policymakers and other officials pushing for an eventual resolution. However, time spent as a refugee waiting in a tent in the rain will drag on and on, day after waterlogged day.

***

Photo by the European External Action Service via Flickr.

Shane McCarthy (MPP '17) is a freelance writer and former senior online editor at the Georgetown Public Policy Review.