Voter suppression in the 2018 midterms exposed stark differences in how elections are run across the country. A national vote by mail system would restore some basic faith in our democracy.

What’s going on with our elections?

In Georgia, Republican gubernatorial candidate Brian Kemp called his opponent’s refusal to concede, “a disgrace to democracy.”

But the real threat to fair elections started months before, when Kemp, who was Georgia’s secretary of state, purged over 660,000 voters from the rolls between 2017 and Election Day 2018. In North Dakota, officials purged thousands of Native Americans voters for only having a post office box address; in Arkansas and Virginia, officials removed thousands of legitimate voters based on inaccurate information about felony convictions and who moved out of the commonwealth, respectively. Even if voter suppression is not always instrumental in the final election outcome, it deteriorates an already thin and waning trust in government and the democratic process. When countries run elections like these on the other side of the world, the United States calls for United Nations election monitors.

There are some promising trends—Florida enfranchised nearly 1.5 million people with the passage of Amendment 4 and a few states passed same-day or automatic voter registration. But these measures don’t go far enough.

One of the best ways to strengthen the fairness, accessibility, and security of our voting system is vote by mail. Here’s how it works: Registered voters receive their ballots by mail far in advance of Election Day, as if everyone were absentee voters. After filling out their ballots, voters can choose to mail them back or drop them off in-person at a designated vote center. No Disneyland-length lines, no struggle to get time off work, no hiring sitters for the kids, no long car or bus ride to the polling place, no extensive planning necessary. Vote by mail is maximized convenience without sacrificing security, and it does wonders for turnout. It’s a solid first step toward rebuilding the broken trust between people and the institutions that are supposed to represent them.

What issues does vote by mail address?

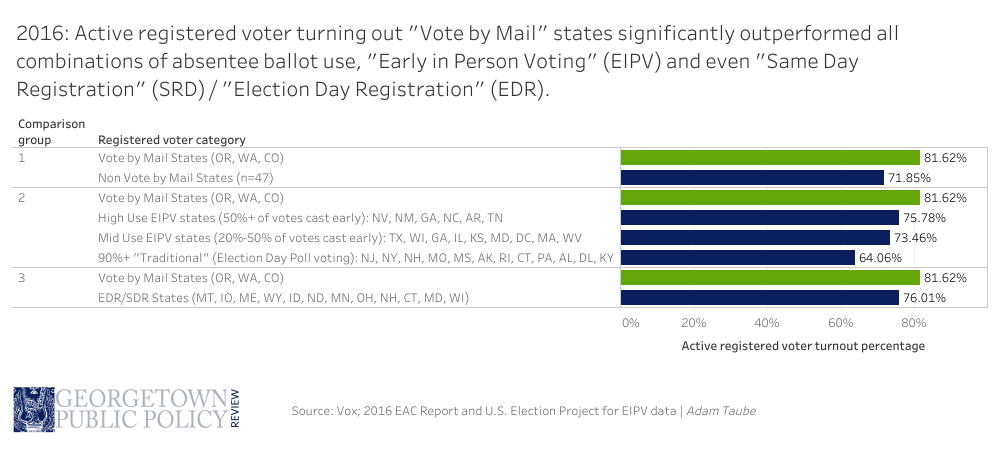

First pioneered by Oregon nearly 20 years ago, just two other states have established all-mail elections since: Washington in 2011 and Colorado in 2013. Today, these three states have among the highest voter turnout in the country. As the counts among voting-eligible populations stand at the time of this writing, Washington witnessed 58 percent turnout (eighth highest nationwide), Oregon saw 61 percent (third highest nationwide), and Colorado saw 62 percent (second highest nationwide). None of them had high-profile showdowns to garner the kind of mainstream coverage that Texas, Florida, and Georgia received, and yet they outperformed all the nationally-hyped contests.

Sure, it was a historic high-participation midterm season, and factors other than access drive turnout. However, average turnout across the trinity of all-mail states exceeded average turnout in the 47 in-person voting states in the 2014 primaries, the 2014 general, the 2016 primaries, the 2016 general, and now, the 2018 general. It may be a small sample size of elections, but the early returns of vote by mail are promising. Furthermore, the biggest turnout growth appeared in the primaries and midterms, where turnout usually suffers to the advantage of more extreme candidates.

Vote by mail also energizes turnout among people with short or nonexistent voting histories, who are among the intended targets of voter suppression. In a recent study that analyzed the first vote by mail election in Colorado, 18 to 24 year old voters outperformed model predictions by nearly 12 percentage points. Researchers found that turnout gains from all-mail voting in Washington shrunk the gap between high-frequency and low-frequency voters.

However, there are some caveats to clarify. It’s possible that while vote by mail increases overall turnout, it does not necessarily make the participating electorate more representative of the voting-eligible population, as researchers found in an early look at Oregon’s vote by mail system. This has important implications for minority voters who are systematically disenfranchised by voter suppression. Organizing efforts to get out the vote must continue to reach new voters, especially since casting the first vote tends to be habit-forming. Vote by mail would make organizers’ efforts easier by eliminating some of the most significant obstacles to the ballot box, such as finding time off work or getting to a distant polling place.

Finally, any election analysis without discussing security is incomplete. In the wake of Russian interference in the 2016 elections, security is top of mind for responsible election officials. States like Georgia and Louisiana, which have no paper trail to verify votes if their electronic systems fail, risk manipulation and mismanagement. Computers that program elections are connected to the internet (even if voting machines aren’t) which exposes states to substantial security risks. At this year’s Def Con—the largest hacking conference in the world—an 11 year old was able to change election results on a simulated state website in just 10 minutes.

Is vote by mail a silver bullet?

Vote by mail is not a perfect system, and its shortcomings should be brought out. For instance, vote by mail doesn’t solve the problem of signature-matching, the practice of comparing signatures on the ballot with the original signature on the voter registration rolls. Signatures change for a whole host of reasons: last name changes after marriage or divorce, signing in English as a second language, declining eyesight, and accidents or disabilities which affect fine motor skills may all contribute to signature-matching errors. Election officials who make signature-matching determinations often have no special training and use varying standards state-by-state. Officials aren’t always required to notify voters who fail the matching test. It doesn’t help that even the science of handwriting analysis is in dispute.

Furthermore, not all voters have a permanent residence or can afford stamps. Homeless people are almost completely excluded from the electoral process to begin with, and vote by mail does nothing to include them. Non-voters are the easiest for politicians to ignore because there are rarely electoral consequences for it, yet non-voters are often the people in need of the most help. Additional reforms to make voting more inclusive and less costly must be introduced alongside a vote by mail system to address its deficiencies.

That said, voting is necessary, but not sufficient, to establish a functioning, inclusive democracy. Democracy needs a free press, fair courts, freedom of speech, rule of law, individual rights, and a thriving civic culture. All these institutions are under serious threat or have already backslid into dangerously undemocratic territory here and abroad. Protecting these critical foundations is often controversial and complicated, raising important questions. How is justice determined in our courts given what we know about human error and biases? When does speech constitute a physical danger to others?

Vote by mail represents something positive and concrete policymakers can achieve in a time of intense public distrust of government. Senator Ron Wyden and Representative Earl Blumenauer of Oregon have already proposed a national vote by mail system, which should be passed into law on its own or perhaps as a component of new civil and voting rights acts. Until Congress passes substantial reforms to the electoral system, the democratic deficit between states will continue to grow. To paraphrase Abraham Lincoln, the country cannot exist half-authoritarian and half-democratic—if left divided, “it will become all one thing or all the other.”

Photo by Mark Gunn via Flickr.

Online Editor Devin Edwards is a Class of 2020 MPP candidate focusing on urban policy. He is from the beautiful state of Oregon, where he worked as a data analyst and volunteer teacher. At Georgetown, Devin researches wealth-building policies for the McCourt Policy Innovation Lab and hopes to continue advocating for inclusive and empowering urban design in the future, whether in the nonprofit space or local government.