The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is one of the world’s most significant data privacy laws to date. The GDPR applies to almost all companies that collect data from European residents, even those that are based outside the European Union. As U.S. companies adopt practices to comply with the GDPR, U.S. federal and state legislators are looking to formulate privacy legislation in the United States as well.

The General Data Protection Regulation

On May 25, 2018, the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect, integrating European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA) nations under a new privacy framework. With the GDPR, the European Union has implemented comprehensive data security and privacy regulations on almost all companies that collect personal data from EU or EEA residents. Any violation of the regulations comes with a significant penalty: up to four percent of a company’s global annual revenue or 20 million euros, whichever is greater. With the stricter regulations, the European Union has affirmed individuals’ rights to access and delete personal data and has heightened data breach notification and consent requirements for companies.

Privacy policy in the United States

Unlike the European Union, the United States has not yet implemented a universal privacy framework. Currently, U.S. privacy laws vary by sector, with separate laws like HIPAA, COPPA, and GLBA safeguarding certain information pertaining to health, children, and finances, respectively. Over the past 16 years, all fifty states have individually passed laws governing data breach notification, and many states have passed additional laws requiring data security practices such as encryption.

However, the United States may be experiencing a turning point in privacy. On June 28, 2018, California passed the California Consumer Privacy Act, thus becoming the first state to introduce comprehensive restrictions on data collection and processing. Among other provisions, the new law requires companies to allow consumers to access and delete personal information—defining “personal information” as any data that could be associated or linked, even indirectly, with an individual or household. Acknowledging that certain provisions might conflict with existing privacy laws, the legislators instructed that the stricter law would prevail in the event of a contradiction.

California’s inaugural passage of a state-level privacy law could put pressure on Congress to pass federal privacy legislation. As other states consider following California’s lead, some privacy advocates have brought up concerns with the development of a potentially inconsistent “patchwork” of state laws. They assert that a federal privacy framework is necessary to provide baseline protections for consumers, regardless of location or platform.

While the federal conversation around privacy policy has existed for years, Congress has recently faced stronger public demand to enact more substantial legislation. As a result, U.S. Senators Ed Markey (D-MA) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) introduced a bill in April 2018 to formally define privacy expectations for internet users. Additionally, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and John Kennedy (R-LA) are planning to sponsor legislation that increases consumer options for data sharing and mandates companies to provide data breach notifications within 72 hours. As Congress continues to hold hearings and events on privacy, other members of Congress might introduce bills in the near future.

Regulatory enforcement

For the past two decades, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has served as the primary enforcer of consumer privacy protections under its authority to prohibit “unfair or deceptive acts or practices.” Under Section 5 of the FTC Act, the agency has brought cases against companies such as Uber, Lenovo, and D-Link.

However, the FTC has faced some challenges in enforcing data protection. In June 2018, the FTC lost a data security case against former cancer testing facility LabMD. In the ruling, the Eleventh Circuit assumed arguendo that LabMD had participated in negligent or unfair data security practices, but declared that the FTC’s cease and desist order was vague and therefore unenforceable.

As the FTC does not have broad rulemaking authority under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), it faces substantial limitations in creating regulations. Subsequently, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)—which does have APA rulemaking authority—adopted federal broadband privacy standards exclusively for internet service providers (ISPs) in 2016. However, the standards never came into effect, and the FTC reasserted its jurisdiction over consumer privacy protections the following year.

Upon nullification, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai and then Acting FTC Chairwoman Maureen Ohlhausen both contended that exclusively regulating ISPs such as Verizon and AT&T—and not online edge providers such as Netflix and Facebook—would harm consumers through gaps in regulation and give edge providers an unchecked competitive advantage to collect data. Soon after, the FCC and FTC entered a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in December 2017 to jointly review consumer privacy protections.

However, without APA authority to pass data privacy regulations, the FTC’s capacity to fully enforce consumer privacy remains in question for some officials. On this issue, several FTC commissioners, including Rohit Chopra and Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, spoke at a July 2018 House Energy and Commerce hearing on the challenges of enforcing privacy cases without greater authority, funding, and personnel. Although the FTC has traditionally led federal consumer privacy enforcement, Congress could see a need to review privacy enforcement in conjunction with any comprehensive privacy reform.

“Seismic shifts in digital technology”

In June 2018, the Supreme Court demonstrated that the pervasiveness of modern technology may require a reexamination of existing rules. In Carpenter v. United States (2018), the court ruled that the Fourth Amendment protection against “unreasonable searches and seizures” applies to cell phone location records (otherwise known as cell site location information, or CSLI). In this case, the U.S. government had accessed Timothy Carpenter’s cell phone location history without a search warrant under the third-party doctrine, a legal theory that holds that individuals who voluntarily give data to third parties surrender their expectation to privacy.

In this specific case, the Supreme Court rejected the argument that the U.S. government does not require a warrant to access CSLI under the third-party doctrine. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that CSLI supersedes traditional observation in its scope and omnipresence and that individuals do maintain some expectation of privacy in this context. Chief Justice Roberts opined that “seismic shifts in digital technology” can lead to different applications of the law.

While these “seismic shifts in digital technology” compel scrutiny into current privacy practices, not all privacy advocates believe that the United States should adopt an exact replica of the GDPR. Critics argue that the GDPR hurts small businesses without sufficient legal resources and personnel to comply with more complex regulations. For example, some U.S. websites and companies, including the LA Times and Chicago Tribune, temporarily or permanently blocked access to European users upon the law’s implementation, due to compliance issues. And three months after the implementation of the GDPR, the full effects of the regulation on U.S. privacy, competition, and innovation are still unknown.

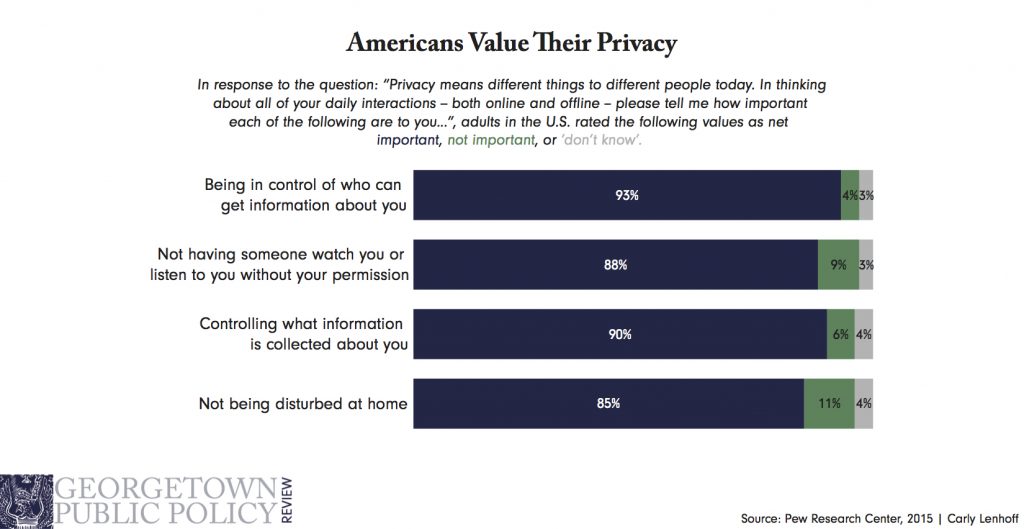

With the growth of internet-connected devices and quantity of data sharing, discussions of a baseline federal privacy standard are increasingly relevant. In 2014, the Pew Research Center found that 90 percent of Americans believed that it is important to have control over what personal information is collected. However, only 31 percent of Americans believed that the government would keep their data private and secure, and only seven percent of Americans believed that online advertisers would keep their data private and secure. It remains to be seen how the recent media attention to privacy and data breaches will change these numbers. However, there is an unequivocal national interest and necessity for more coherent privacy standards, and many policymakers and government leaders are taking note.

Photo by Dennis van der Heijden of Convert GDPR

Caitlin Chin was a senior online editor for the Georgetown Public Policy Review and a M.P.P. candidate at the McCourt School. She holds a bachelor's degree in government and Spanish from the University of Maryland.