Over the past 18 months, the solar industry has been in transition. Once flush with cash, living on the leading edge of energy innovation—at great cost—the solar industry is growing more financially stable and sustainable. Increasing pressure from investors and stakeholders indicates solar developers and distributors are capable of turning profits, but this transition is causing issues for established entities, and for potential innovators and disruptors. At such a delicate moment for the industry, policy at a federal and state level plays a very important role in helping to nurture sustained growth.

Background

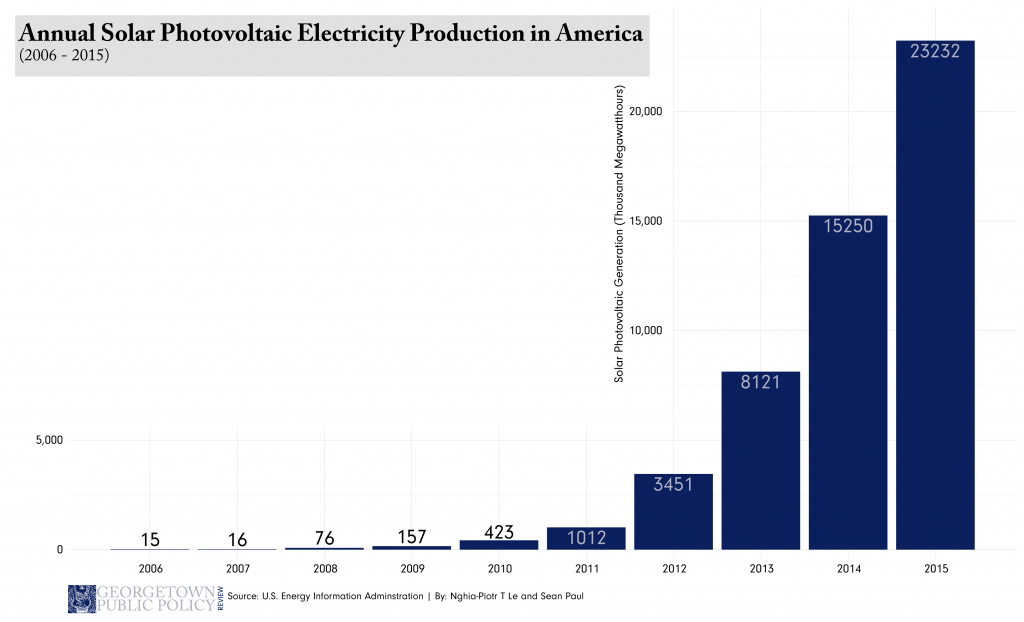

The rising interest in solar energy has caused the industry’s capacity to multiply a thousand times over in the past decade. The launch-pad for the solar industry was the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The Bush-era energy bill authorized the 30% Solar Investment Tax Credit (ITC), which shaved the top off the cost for a solar array and also signaled state and local regulators to build similar policies. The lucrative tax structure on the federal level, combined with some disparate buy-in on the state level, has drawn commercial and residential investors into the green revolution. Billions of dollars flooded into solar companies from private investors, the ITC, and some extra subsidies and credits, sending the industry charging towards far-reaching development, production, and leasing portfolios.

Not surprisingly, however, the ITC would not persist in perpetuity. The ITC was slated to expire at the end of 2016, needing to be reauthorized–as it was in 2008. While President Obama sought to reauthorize it indefinitely, the ITC discussion got tied up in separate debates over the Export-Import bank and the oil export ban, facilitating a compromise. The ITC was reauthorized indefinitely, but with the credit level dropping from 30% to 10% starting in 2020.

Policy impact on the industry

The government is sending signals to the private sector that the era of free money is mostly coming to a close. Luckily, the private sector was out in front of the issue. The years before and after the Great Recession were marked by glamorous Initial Public Offerings, exciting financial innovation, and notable sentiment throughout the solar industry. But after the honeymoon period ended, fiduciaries and shareholders rolled up their sleeves and started looking inward. The time to report earnings and demonstrate profits had come.

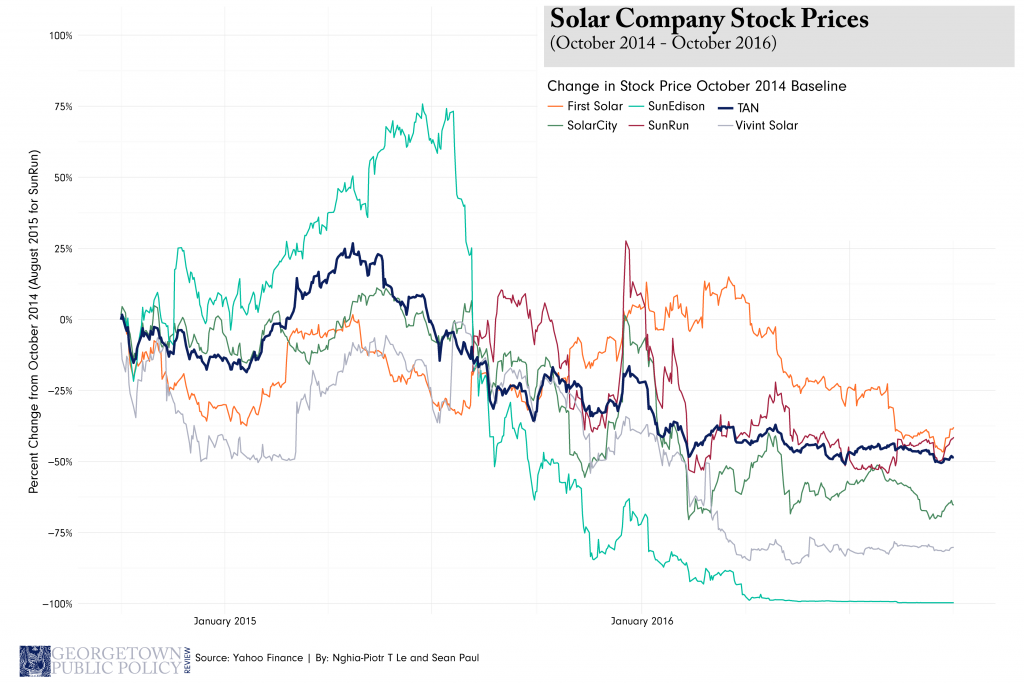

There is, for example, the demise of the much-beloved SunEdison. Once considered the most innovative renewable energy company in the country, SunEdison pursued a strategy of rapid growth by investing a staggering $18 billion in acquisitions leading up to July 2015. In a marketplace that is now demanding financial viability from solar providers, SunEdison was digging itself deeper into the hole with additional acquisition promises. Their shares declined, and by April 2016, SunEdison declared bankruptcy, crushed by over $11 billion in debt.

The implosion of SunEdison sent shockwaves through the industry, causing companies and investors to wring their hands even harder. While SunEdison was shedding its stock value, SolarCity, Elon Musk’s solar company, was dealing with its own set of issues. SolarCity tripled the interest rates on its bonds from 2014 to 2016 in an effort to raise cash to cover its $3 billion in debt obligations. Add onto this the ongoing competition from low oil prices; major solar companies began to show signs of glut and limited financial sustainability.

The impacts spread down the chain

The rocky transition spells trouble for more than just the major distributors. The drawback in investments has trickled down to young startups such as Yeloha. Pioneered by a pair of Israeli innovators and headquartered in Boston, Yeloha was a startup that sought to democratize energy investing. The company built an online platform through which individuals could invest in others’ solar arrays and take advantage of a portion of the clean energy profits. The peer-to-peer investment model was the core of Yeloha’s plan to expand access to solar energy to the 35% of Americans who do not own a roof to put them on.

Yeloha secured $3.5 million in seed funding in April 2015 to get the company off the ground. Riding a tide of media coverage, Yeloha expanded out of New Hampshire and built up enough momentum to push towards New York. They built up a following of thousands of eager customers-to-be and established relationships with public utilities.

Yeloha hit the market at a delicate moment. Expanding into additional states meant dedicating resources and personnel to working with additional regulators and public utilities. When each state has its own regulatory framework, each state embodies its own set of challenges. As Yeloha was ramping up operations, financiers turned their back on the solar industry, causing the company’s potential funding streams to run dry. By May 2016, Yeloha, an innovator and potential market disrupter, shut its doors.

State-level collaboration

While it is true shares are down and a few companies have gone bottoms up, there are some fundamentals we can count on. The most important of these is the certainty of demand moving forward. The price per kwh of solar energy continues to drop as the popularity and accessibility of solar services and companies continues to rise. Baseline demand is a solid wall that the industry is already leaning up against to maintain revenue levels.

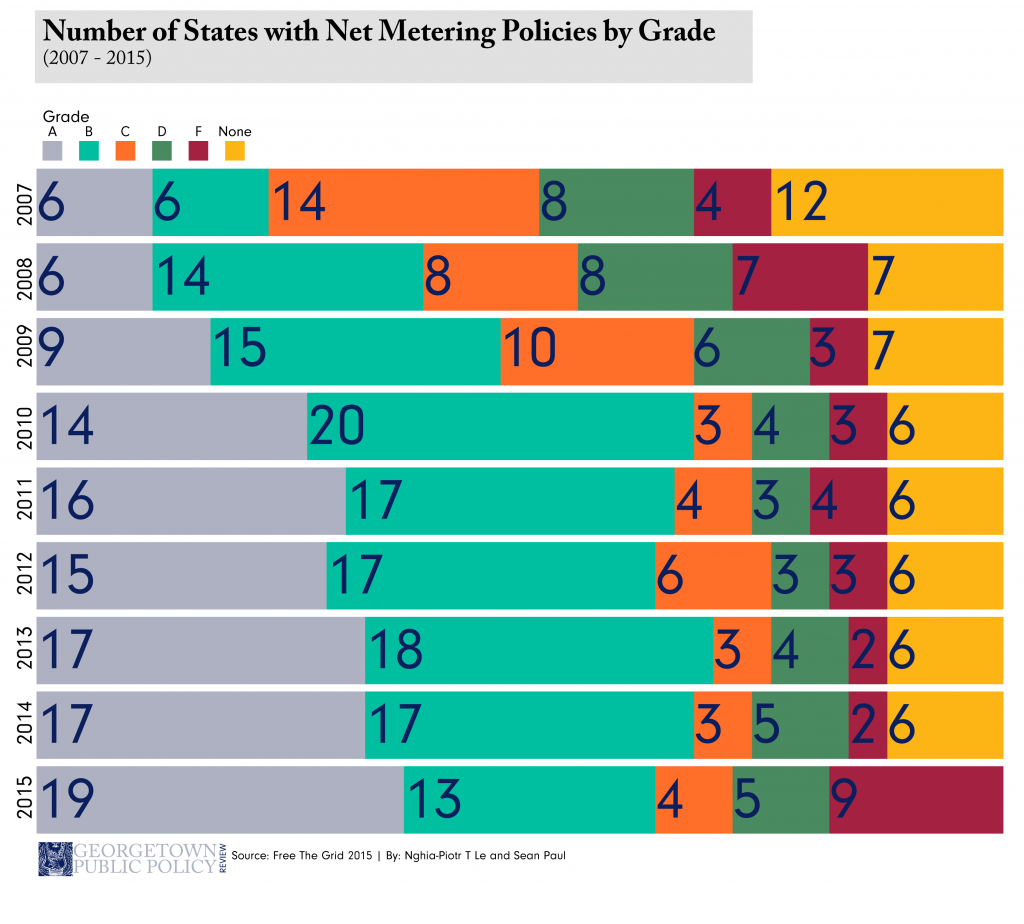

Markets crave consistency. Steady, well-crafted, and well-targeted policy has the potential to convey clarity and confidence, especially across state borders. One critical example of this is the development of state-level net metering policies. Net metering, a mechanism that was enabled by the Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act of 1977, is the regulatory framework that allows residential energy producers to sell excess capacity into the grid. Through net metering, homeowners are able to sell some of the solar energy their arrays produce, making their investments more profitable.

Net metering has historically yielded mixed results. Because it is administrated on a state level, there is a lot of room for variation. There has been a substantial effort in recent years to standardize these policies to limit confusion and eliminate barriers to investment across state borders.

Conclusions

Increased integration of state-level policies will further drive innovation in the solar industry moving forward. Further, building a coherent framework in this way will allow fledgling innovators—the Yelohas of tomorrow—to chart a path forward in a more certain environment. In this transitory period, the market for innovation and disruption can be very constricting. Regulators play a role in this market and ought to continue streamlining policies that frame the solar market and allow diverse and innovative investment.

Sean is a first-year Master of Public Policy candidate at Georgetown University's McCourt School of Public Policy. From New York, Sean earned his Bachelor's degree in Economics and Sustainability Studies at Stony Brook University. His policy interests include economic, environmental, and regulatory policy. Sean has experience working in the Federal Government and the United States Senate, and currently works in performance analysis. Follow him on twitter: @seanjpaul