Mexico has long been regarded a rising star among Latin American emerging market economies. President Enrique Peña Nieto’s major constitutional reforms prove Mexico is moving in the right direction. However, as Peña Nieto launches into the second half of his term, optimism is fading. Many reforms have produced discouraging outcomes and scanty secondary laws have left significant issues unresolved. Among the set of structural reforms that were passed by Congress, the overhaul of the education system has proven to be the most limited in its scope. Moreover, what little opportunity remains for improving the quality of Mexico’s education system is being stalled by opposition from the teacher’s union.

Mexico’s educational performance has improved in recent years and enrolment rates have increased – the proportion of students entering first grade that later finish sixth grade exceeds 96 percent and the literacy rate for the population aged 15 to 24 years is close to 100 percent. However, OECD (Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development) performance indicators show that Mexico remains behind global comparatives. Improving the quality of education has long been regarded a top priority for the incumbent government and much remains to be done.

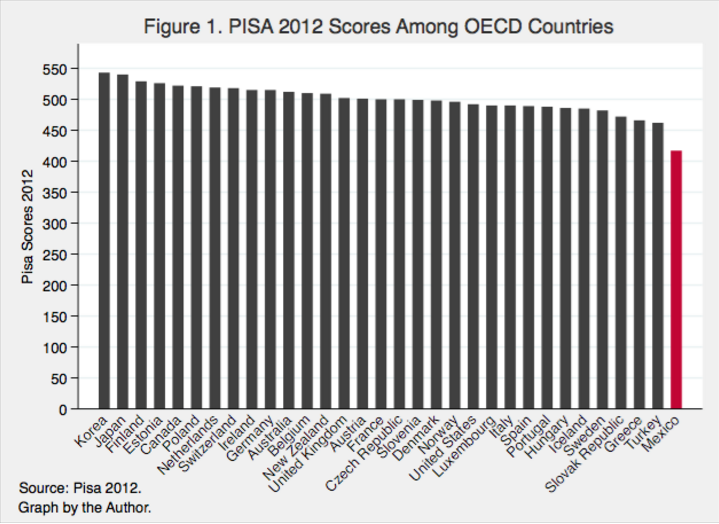

At present, Mexico’s student performance ranks among the worst among the OECD countries, as displayed in figure 1. According to the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2012 report, Mexican students fall short in critical reading, math and science skills, with alarming shortcomings in math. While 41 percent of Mexican students did not reach the basic level reading comprehension skills required by PISA, 55 percent did not achieve the basic level of math skills. Mexican student’s overall poor performance is endemic throughout the system; for example, math tests fall 81 points below the OECD average, the equivalent of having a 15-year-old student falling behind nearly two years of formal schooling.

Mexican students also tend to drop out of school very early. While primary education is practically universal, less than 40 percent of young adults aged 25-64 have graduated from high school – almost half the average among OECD countries. Mexico also has one of the highest secondary education dropout rates. Only 53 percent of 15-19 year-olds are enrolled in upper secondary education, compared to an average of 84 percent in other OECD countries (Kattan and Miguel: 2014).

Additionally, many Mexican schools, particularly in poorer rural regions, as in the South, lack basic personnel and infrastructure, such as school supplies, electricity, sewage and accessible roads. Mexico has the highest student to teacher ratios in primary education among OECD countries –28 students per teacher– and in marginalized communities, this ratio can double as the majority of schools in poor municipalities operate with only one teacher per two or three different school grades. What is more, education inequality is perceptible among indigenous students and students with low socioeconomic status. According to OECD data, performance gaps in reading skills have increased for students where the language spoken at home is different from Spanish, from a 71 score point difference gap between indigenous and non-indigenous students in 2000 to a 95 score point difference gap in 2009.

Government spending on schooling has not translated into gains in the quality of education. While Mexico spends 22 percent of public non-capital spending on education, the highest share in the OECD, spending per student is only one-third of the OECD average and the second lowest percentage among OECD and partner countries. Mexico devotes nearly 94 percent of its education budget towards teachers’ salaries and staff compensation, well above the 64 percent OECD average.

Most of the blame for Mexico’s poor education system is placed on the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE), which until recently interfered in all major educational programs and enjoyed monopoly power over labor relations between federal authorities and teachers. Historically the SNTE, with the assistance of state governments, was able to manage the hiring and promotion of teachers, without taking into account any established recruitment or training standards. Some arrangements between unions and governments even allowed the sale and inheritance of teachers’ posts (Zapata, 2014), exposing the lack of transparency and governance across Mexico’s education system.

To combat this major problem, on February 25, 2013, President Peña Nieto adopted the Education Reform Bill. Viewed by many as a first step towards overcoming corruption and inefficiencies in the education system, the Education Reform Bill attempted to put an end to Mexico’s detrimental education system and was hailed by Peña Nieto’s as “the foundation for transforming Mexico” (Nieto, Enrique. “Felicito a Los Diputados Por La Aprobación De La Reforma Educativa. Con Ella, Estamos Sentando La Base Para Transformar a México.” Twitter. December 20, 2012.). Nonetheless, to this day the Education Reform Bill (from here known as the Bill) has proven disappointing. What went wrong?

The changes made to Articles 3 and 73 of the Constitution had at its core the proper evaluation of teachers, a system where merit would be the criterion by which teachers were appointed and the promise that teachers could be fired if they failed to meet standard. While schools continued to be administered by the states and were given more autonomy over how they handled their own resources and defined their own curriculum, the federal government took more responsibility for teacher certification, evaluation and salary distribution.

Among other things, the bill created a new independent body called the Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación (National Institute for the Evaluation of Education) to periodically evaluate teachers, while the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) is responsible for designing, organizing and implementing teaching curriculums. In addition to teacher evaluations, the reform package included the creation of a merit-based pay and promotion system, tests for new teachers entering the field, and more federal oversight. These constitutional amendments gave the government, rather than the SNTE, control over the hiring and firing of teachers, halting a structure where only union members can become teachers and where they are allowed to hold guaranteed lifelong posts without ever being tested for their performance.

However, two years have gone by and these constitutional adjustments have not yet been able to amend the Achilles heel of the Mexican education system: instead of ensuring standardized quality education through a single national system, the incomplete decentralization has allowed local state authorities to establish their own guidelines for the functioning of education institutions.

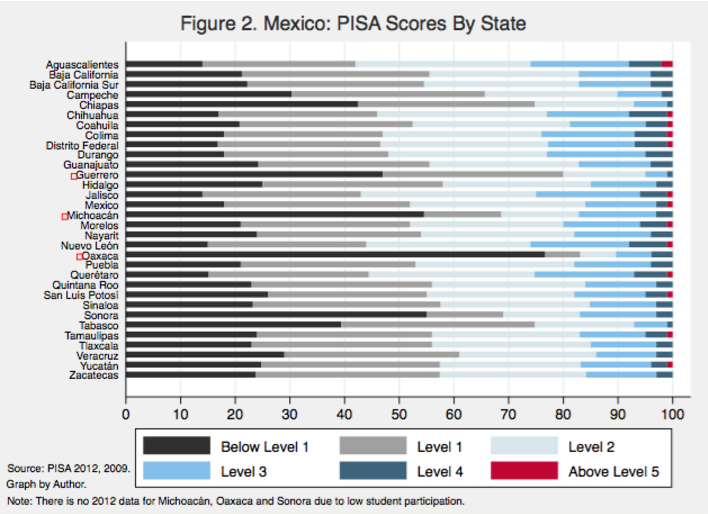

Shortly after the bill came into effect, thousands of teachers took to the streets to oppose the reform (Webber, Financial Times, 2015). Dissident teachers belonging primarily to the Section 22 of Oaxaca’s SNTE, known as the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE), abandoned their classrooms in the southwest states of Mexico to oppose teacher evaluations. Even worse, classes in thousands of schools across the country were suspended for months due to teacher protests. It is estimated that children from Oaxaca, Michoacán and Guerrero have lost up to 85 days of the school year (Sanchez, Reforma, 2015); these states –as displayed graphically in figure 2–, already exhibit the highest levels of educational backwardness in the country, according to PISA 2012 and 2009 results. In some southern municipalities, class suspensions became so common that parents, feeling powerless over their children’s lack of education, started to replace dissident teachers in local public schools, without undergoing knowledge based tests or any kind of pedagogical training (“Padres De Familia Dan Clases En Oaxaca Ante Paro De Maestros.” El Economista, August 27, 2013,).

The government’s incapacity to manage the execution of the education reforms was exacerbated as mid-term elections approached on June 7, 2015. On May 29, 2015, the Ministry of Education suspended temporarily teacher evaluations that were due to take place for the first time in July. Under the claim that “new elements” needed to be taken into consideration in the evaluation process; the government forfeited the most important element of the Education Reform to maintain political capital. Fortunately civil society, education advocacy groups and parents responded with sweeping criticism, arguing for evaluations to be reinstated after the election period had concluded. Nevertheless, while the SEP claims that the reform is back on track, the low teacher participation rates during the evaluation process do not support the government’s optimistic reports.

Both the CNTE and the SNTE are backing-up an education system that involves maintaining the status quo by serving its leaders’ interests. The union’s ability to mobilize tens of thousands of teachers gives it enormous power over state governors and undermines Mexico’s political stability. While certain aspects of the CNTE’s criticism towards the current administrations can be understood in the sense that it takes much more than merely installing teacher evaluations to improve the quality of education, resistance to reforms will prolong educational underachievement in Mexico and set back social and economic development.

In the end, it is important to keep in mind that the evaluation process is a first step and two years are not sufficient to make assertions about the final outcomes and impacts of a reform of this magnitude.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The circumstances in which the Education Reform developed suggest that it is necessary to carry out important changes besides monitoring systematic student and teacher evaluations. First of all, in order to implement policies that improve the quality of education, it is imperative to discuss the relevance of the educational model. In this respect, the policy instrument presented by President Peña Nieto disregards completely the current teaching model. Beyond a brief mention on improving the quality of education programs, none of the six objectives of the reform appear to alter the pedagogical model. Other relevant matters include the lack of governance, the absence of a coherent funding strategy, and systematic monitoring and cost effectiveness of the education system.

Thus, in order to attempt to truly reform the Mexican education system, the following actions should be considered: first and most importantly, it is essential to deliver a curriculum that is no longer based on pure memorization but instead emphasizes critical thinking and prepares young people to successfully address the complex world in which they live. It should be noted that other countries with strong teacher’s unions like Singapore and Finland have excellent educational performance because of their curricula, high teacher quality standards at entry level, and not just measuring teacher effectiveness. In concert, professionalization of the education system through teacher training programs and a merit-based organizational scheme is key for improving the quality of education; school leaders and teachers are to place student learning at the center of their efforts to improve the education system. Finally, governance within both the federal system and local state authorities needs to be prioritized. It is necessary to restructure the education budget so that there is more money going into infrastructure. In addition, transparency and accountability in education funding are both required to identify which sectors have greater influence over quality improvement and to provide a more equitable distribution of learning opportunities.

The policies described above involve further legal modifications with higher political costs that must be taken into consideration. Nonetheless, the importance of attaining better quality education is heightened as Mexico strives to move past the Millennium goals.

Bibliography

Kattan, Raja Bentaouet and Székely Miguel. “Dropout in Upper Secondary Education in Mexico.” World Bank Group, Education Global Practice Group, November, 2014

Zapata, Alexandra. “Mapa Del Magisterio De Educación Básica En México.” IMCO. August 1, 2014.

Sánchez, Virgilio. “Repone CNTE Clases, Aunque Pierde 2 Años.” Reforma, November 17, 2015

Webber, Jude. “Mexico Teachers Demonstrate over Reform.” The Financial Times, October 12, 2015, Politics & Policy

Ana Canedo is a Masters of Public Administration student at Cornell University. She earned two bachelor’s degrees in economics and political science from ITAM, Mexico. Prior to Cornell, she worked as Research Coordinator of the Human Capital Division of CIDAC, an independent, not-for-profit think tank. She then served as Project Leader for the creation of the Tabasco Technology Transfer Center for the Energy Reform. She is currently an associate editor of The Cornell Policy Review and her research focuses on human capital, education and employment.

5 thoughts on “Mexico’s Education Reform: What went wrong?”

Comments are closed.