Things seem to be going well for Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto. Within months of taking office, almost every major news organization published an “Aztec tiger” article citing Mexico’s impressive economic growth rate, increased foreign investment, and growing middle class. Even with the inevitable backlash to this “blue skies” reporting in the US, an August poll found that 60 percent of Mexicans approve of Peña Nieto’s performance. The New York Times presented a new spin on the Aztec tiger narrative this week with an article about the growth of young, entrepreneurial expatriates who are moving from Europe, Asia, and the US to take advantage of preferential exchange rates and the sense of novelty that accompanies living in Mexico. At a time of policy upheaval, the country is undergoing economic and demographic changes in ways that go beyond recent reports.

The Times article observes, “Spanish filmmakers, Japanese automotive executives and entrepreneurs from the United States and Latin America arrive practically daily — pursuing dreams, living well and frequently succeeding.” While it notes that many of the emigrants to Mexico are laborers from South and Central America, who have limited recourse to the law or labor rights, the piece focuses on a coterie of creative professionals who are taking advantage of the fact that, as one interviewee says, “Not everyone follows the rules here, so if you really want to make something happen you can make it happen.”

Examining demographic data in detail demonstrates that immigration has clearly increased. Census data from Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) show that the number of foreigners living in Mexico increased by 95 percent from 2000 to 2010. Of the 961,121 foreign-born people living in Mexico in 2010, 738,103 were from the United States. The 2010 Mexican Census reports that the foreign-born population trends young, with about 56 percent between the ages of 20 and 39. While this is a small percentage of the 116 million people in the country, it does suggest that as Mexico grows, workers will continue to vote with their feet. The other side of this story, however, is what is happening within the general Mexican population.

A Changing Demographic at Home

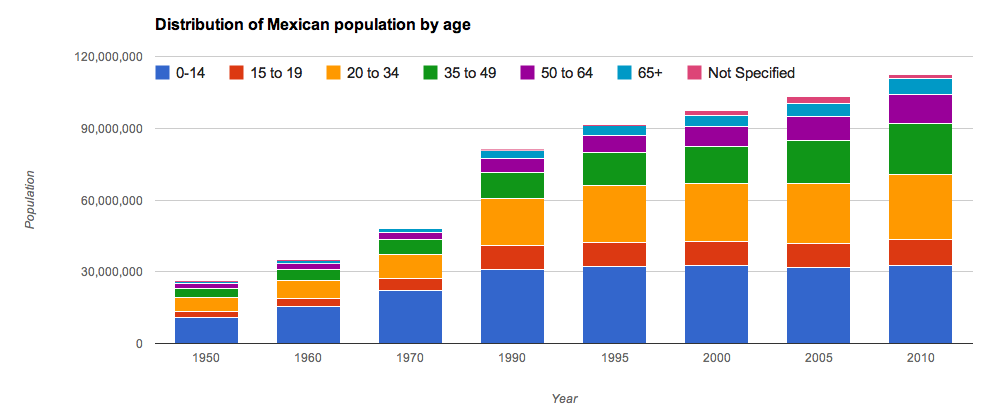

Diving deeper into the INEGI data it is clear that Mexico was changing even before Peña Nieto. For example, census data show that the number of Mexicans in the 20 – 39 age group has stayed fairly constant, while older and younger cohorts have been growing. A notable development for a country that once had one of the highest birth rates in the world, going from 45.7 births per 1000 people in 1960 to 19.2 in 2011 according to the World Bank.

Source: INEGI

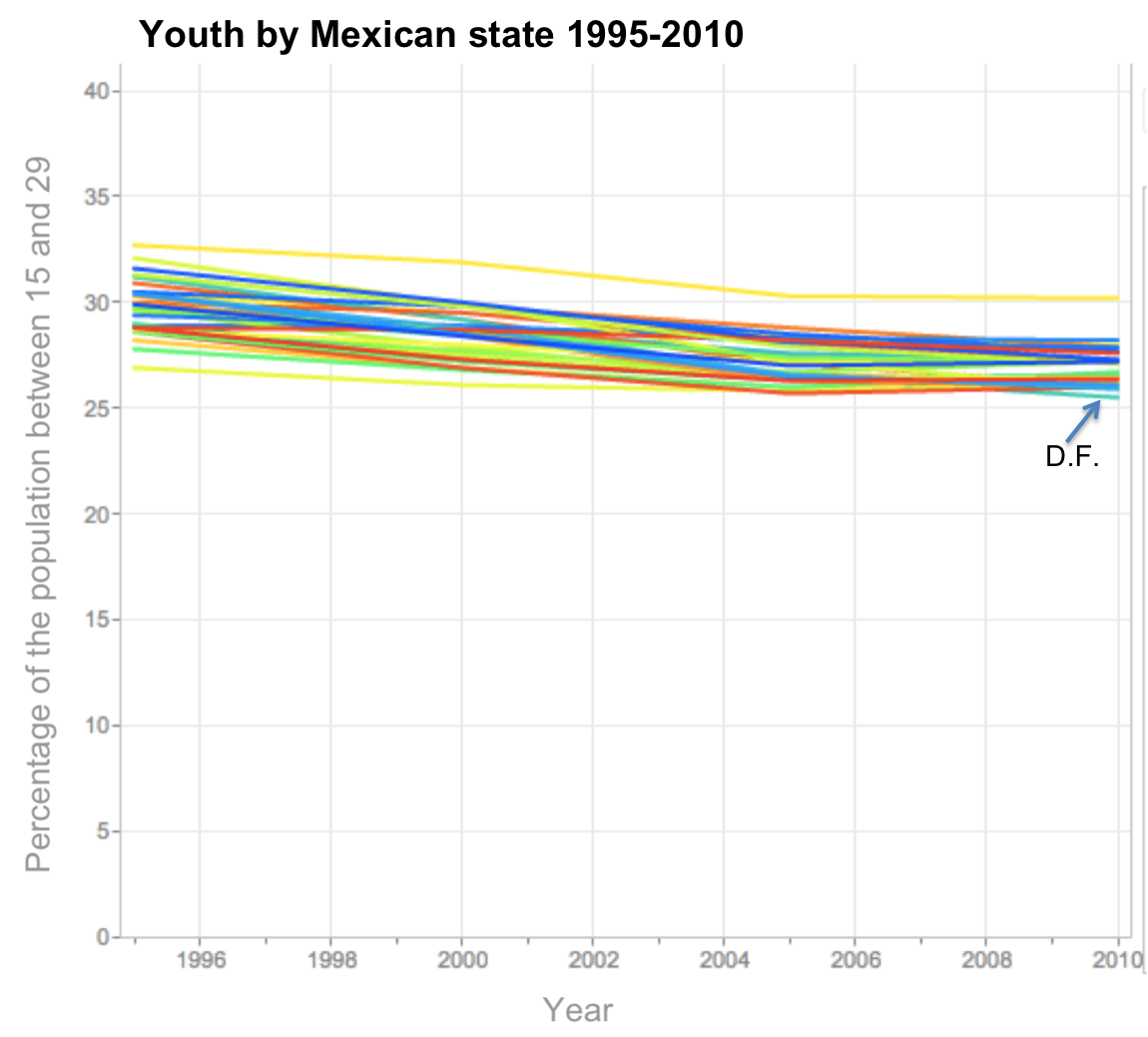

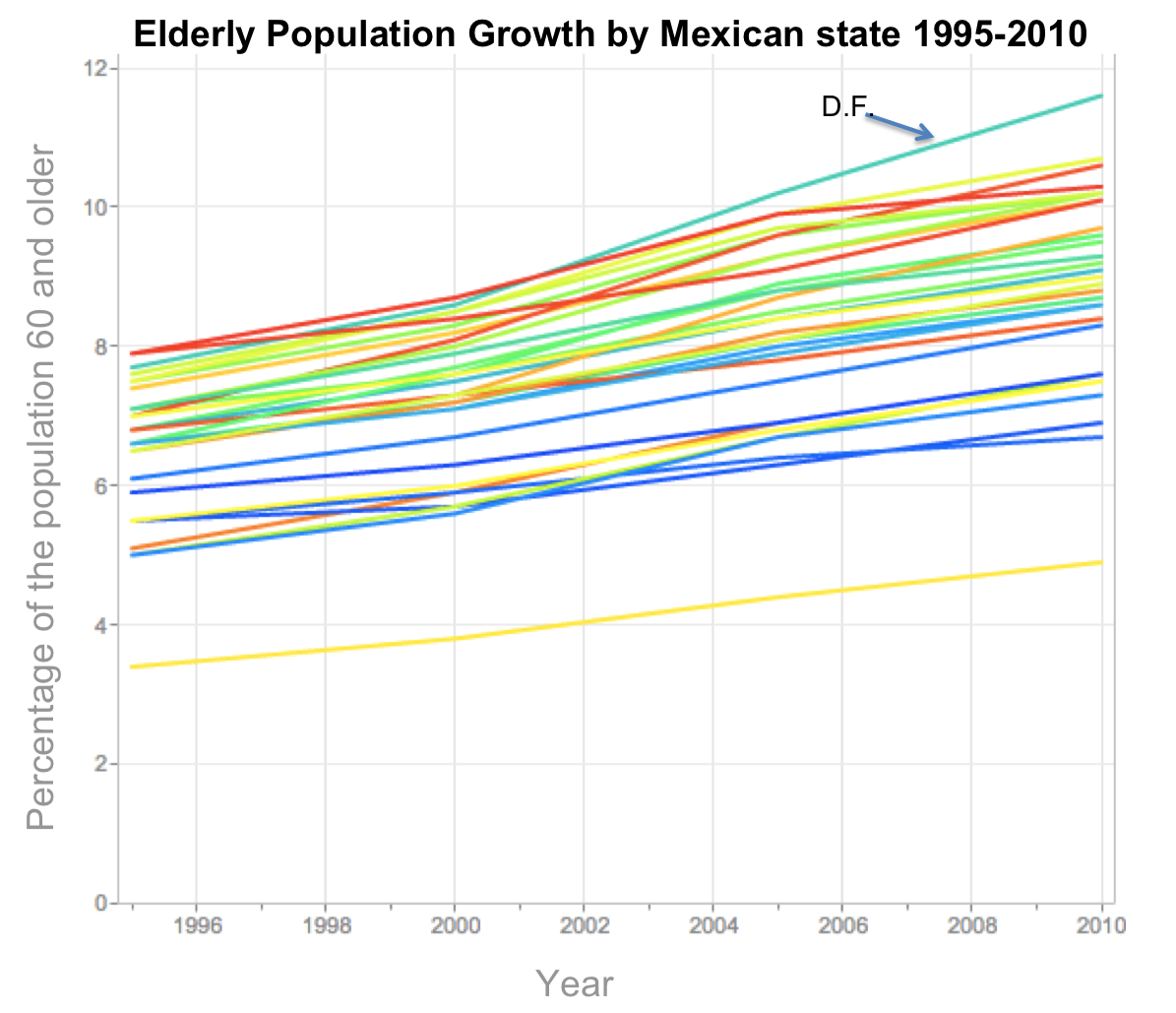

Disaggregating by state also shows a general stagnation for the young native-born population, and steady growth among the 65 and up cohort. Although the young make up a larger proportion of the Mexican population, the share of elderly is, as would be expected, growing. For example, the youth population in Mexico City has fallen from 31.2 percent in 1995 to 25.5 percent in 2010, and this is while out-migration (mostly to the US) among the same age group has declined dramatically. Conversely, the elderly population in Mexico City has gone from 7.7 percent in 1995 to 11.6 percent in 2010. This steady increase over time of elderly Mexicans has implications for who will benefit from the recent high growth rates, not to mention what services the government needs to provide. Combined with the influx of young immigrants, Pena Nieto’s government faces a changing population that will require adapted policies and priorities.

Moving Beyond the Pact

While it is interesting that more people are moving to Mexico at a time of political and economic reform, it is worth keeping in mind that the sentiment of “not everyone follows the rules here” affects more than the small group of expatriate business owners. Large swaths of the Mexican population will experience first-hand the changes from Peña Nieto’s “Pact for Mexico,” a bipartisan reform effort that is being met with mixed reactions. The changes underway as the government works to make itself more transparent and reform its security, judicial, and public service systems will likely be disruptive to both embedded interests and disconnected expat entrepreneurs. The ‘wink-wink-nod-nod’ shortcuts that exist now will be replaced by codified rules enforced by (ideally) accountable institutions.

The rise in immigration to Mexico is only part of wider demographic and migration changes. More data is needed on not just where immigrants to Mexico are from, but how integrated they are in the economy and how many are applying for dual citizenship, which could have implications for raising the tax base and making government more accountable. HSBC rates Mexico sixth in its annual Expat Experiences survey, a random sample of expatriates around the world. Yet the report also notes that, “Mexico seems to be a country where expats pass through rather than settle.”

Being able to attract immigrants is without a doubt a good sign. Although economists disagree about the impact of immigration on the economy, there is some consensus forming around the idea that immigration can produce positive spillovers and beneficial, or at least neutral, economic effects. In fact, the upward trend in the elderly population may eventually signal a need for more immigration to Mexico. The declining birth rate over the last 50 years is likely a sign of increased economic development and changing social norms, which may also attract the sort of young people profiled in the New York Times. However, research suggests that the gains from immigration can be improved through tax participation in host countries. Peña Nieto has struggled to balance many of his more populist reforms with business-friendly tax policy. How this affects the flow of immigrants and the country’s up-and-down growth remains to be seen.

After his initial warm welcome on the international stage, President Peña Nieto is trying to move ahead with his reform agenda, including well-publicized efforts to privatize, or at the very least, modernize the state-owned oil company, Pemex. Whether such efforts will continue to attract foreign interest even amid signs of an economic contraction, and also raise standards among the general populace, will be the next chapter of Peña Nieto’s story.

Jacob Patterson-Stein is a second year Master of International Development Policy student. Prior to attending McCourt, Jacob worked for Thomson Reuters in Washington D.C., the More than Me Foundation in Liberia, and in a rural public school in South Korea. He spent summer 2013 working for the Support for Economic Analysis Development in Indonesia (SEADI) project in Jakarta.

2 thoughts on “Mexico’s Changing Demographics in an Era of Reform”

Comments are closed.